Design – the genesis of a circular economy

I’ll hazard a guess that the last time a kettle, toaster or other electrical appliance in your house broke, you thought to yourself this should be repairable. However, I’m fairly sure you couldn’t easily get it repaired or the repair was going to cost the same or more than a new model.

‘Right to repair’ – it’s a term you’ll hear more and more in the coming months and years. In Australia, the Productivity Commission recently released a draft report on the Right to Repair, looking at consumers’ ability to repair faulty goods and to access repair services at a competitive price.

The EU passed the right to repair into law in March, meaning manufacturers of electronic goods must make their products repairable for at least 10 years. With our Waste Minimisation Act 2008 (WMA) one of the many things under review by the Government, perhaps it’s our turn to get this right enshrined in law.

When we look at design, right to repair is one of the many ways to tackle our rubbish record on waste right from the get-go. Where recycling is largely the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, further up the waste hierarchy – a much modified but still dominant guiding principle created by former Dutch politician Ad Lansink in the 1970’s – we often see repair near the top. It is also a key piece of the circular economy puzzle.

Design and the Circular Economy

The circular economy sits in direct contrast to the wholly unsustainable concept of infinite economic growth from finite resources which is the basis of our current ‘take, make, waste’ linear economy.

Where we need to get to is a circular economy – an economic model where there is no waste, resources are fully utilised, and the maximum value of those resources is then extracted before being fed back into the supply chain. Where a circular economy maintains or increases the value of resources, recycling (with some exceptions) seldom achieves this. It certainly has a place in keeping resources out of landfill, but recycling cannot be our focus moving forward.

Product design needs to lead the charge to this new model – we need to aim to design products to last longer, be repairable, enable products to be easily dismantled for both end of life and refurbishment, and ensure all components are labelled with internationally recognised material identification codes.

Repair is not the only solution

Of course, not all products can be repaired or refurbished which means we must look to other parts of the waste hierarchy. Refusal is the ideal but that’s not always practical and certainly not an option where products are mandated for safety reasons. Through our child car seat recycling programme, SeatSmart, we experience the frustration of a lack of design-led thinking at end of life.

The ideal for child car seats would be the ability to test whether we could safely extend its use once a seat reached its certified end of life – under current safety standards this is around six to 10 years depending on make and model. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge there is no capability to test seats in this way.

Without this, design is critical to help this product be more circular, by improving the design of seats for dismantling and by ensuring all components are labelled. Up to 90% of a child car seat by weight is recyclable plastic and metal however poorly labelled plastic components mean around 15% of the seat can’t be recycled for fear of contamination.

Identification technology is expensive and often unworkable for these largely dark coloured plastics. On the dismantling front, poor end-of-life design makes the separation of seat components difficult, time consuming, and costly with some seats taking over an hour to dismantle fully. Design-led thinking could both increase recovery rates and reduce cost.

Even the humble plastic bottle is an example of design not fully taking the product’s end-of-life into account. While the average clear bottle made of PET is highly recyclable it often has a plastic sleeve around it which must be removed, otherwise (being a different kind of plastic) it contaminates the PET recycling stream. The lid is also a different kind of plastic and must be removed as is the ring which is left behind after the bottle is opened.

However, governments and business are making changes.

Forcing change at the design stage

In June the New Zealand Government announced the phase-out of difficult-to-recycle plastics and some single-use plastic items as part of its waste reduction and circular economy goals. Banning difficult-to-recycle plastics forces a shift to new materials or innovation at the design stage.

These bans are part of the tools available in the WMA but there is a strong desire from many within the industry to see the Act strengthened to include options such as the right to repair, minimum recycled content, minimum standards for longevity (useful for products such as a certain not-fit-for-purpose blender which recently went viral), mandatory labelling, decreasing toxicity and reducing mixed materials.

The opportunity provided by the review, and other changes already being implemented under the Act (like increasing the Waste Levy and bans), plus recommendations such as standardisation of kerbside recycling, will certain push change back up the supply chain to producers and their designers where it belongs, rather than with consumers, councils and the environment.

Ahead of the game

Some companies have already started to think more circularly and are redesigning products, packaging and creating new revenue streams, while a raft of new entrepreneurs are taking advantage of the opportunities for new business models based on the circular economy.

There are commercial flooring companies like Auckland-based Inzide Commercial which combines the use of tiles and patterns to allow for easy replacement to extend the life of flooring, while also using recycled materials and stewarding used product back to the factory to be remade into new carpet tiles.

Global technology giants like Ricoh, Sharp and Fuji Xerox have long incorporated repair and refurbishment into their business models at a local level which then naturally lends itself to easier dismantling at end of life.

Wishbone Design Studio in Wellington create iconic wooden and recycled plastic bikes which are engineered to grow with their young rider, while parts are easily available. What this small sample shows is that it can be done, it just requires the right mindset.

And that mindset is a product stewardship mindset: instead of designing a product simply to be sold, externalising the costs of its life cycle, these businesses consider the whole life cycle, internalise the costs and design their products to minimise their impact on the environment and communities.

Where that mindset is lacking, legislation is combining with consumer demand to drive the change.

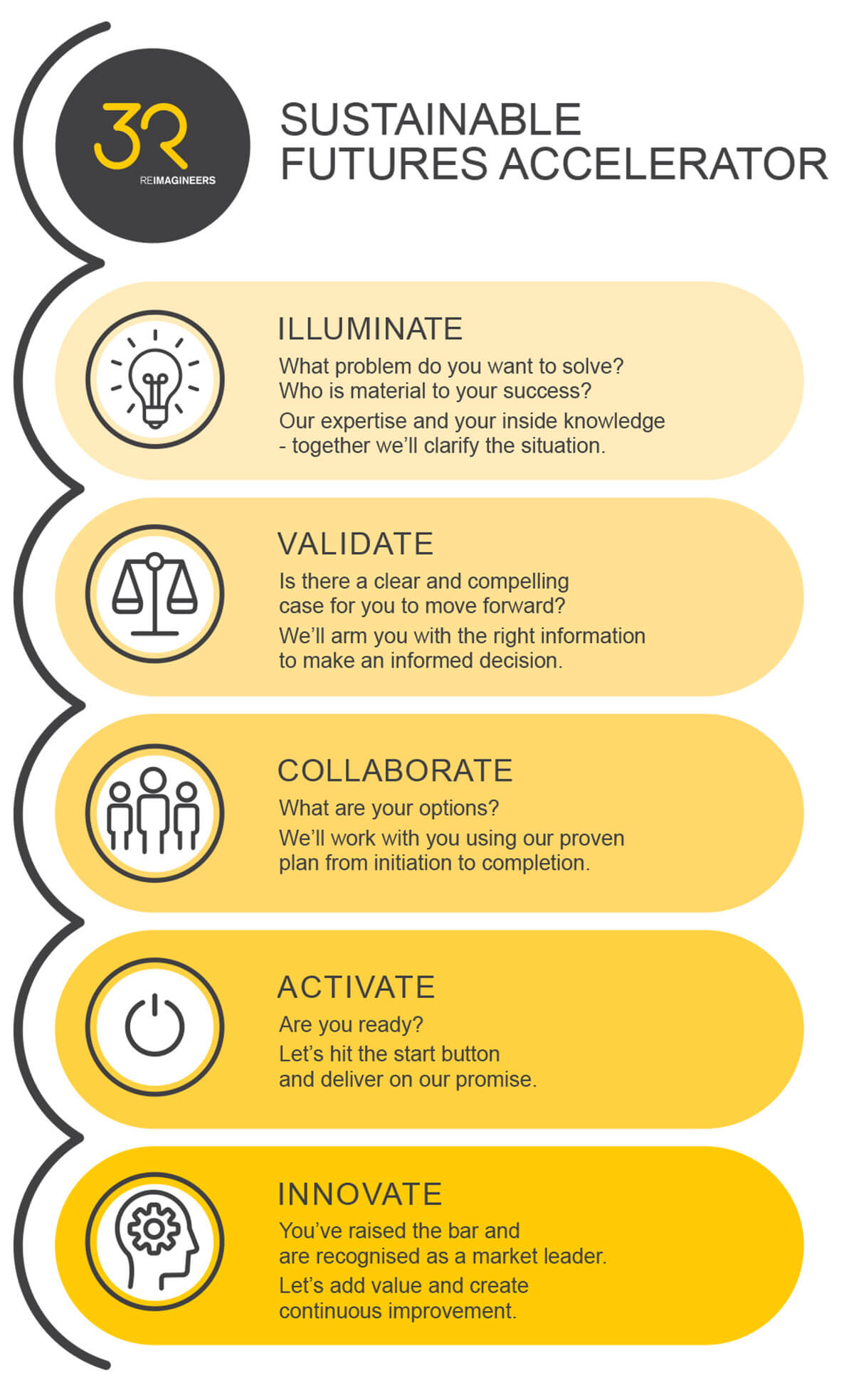

At 3R we are busy working with many different stakeholders to create a circular economy driven by product stewardship and design-led thinking. I’m hopefully that in the years to come we will see an ever-growing shift to a better, more circular way of doing things.

Dominic Salmon is 3R Group’s Business Development Manager

Connect with Dominic on LinkedIn