Food waste – into the great unknown

Published in Bay Buzz

The waste New Zealanders send to landfill every year presents something of a blurry image. We know how much ends up there, but there isn’t good data on what it’s made up of.

Food waste and other organic waste is not only part of this problem but is the main reason waste to landfill contributes 4% of New Zealand’s total emissions – over 3.1 million tonnes worth. This is because when it breaks down in landfill it produces the potent greenhouse gas methane.

Reducing food waste does present some low hanging fruit though (if you’ll excuse the pun) for businesses, and individuals to tackle waste and reduce emissions. It’s a waste stream we are all a part of and can all have a positive impact on.

By the numbers – how much is wasted?

Research from the Kantar New Zealand Food Waste Survey in April 2022 puts the amount of food ending up in household bins at a staggering 100,000 tonnes a year.

To put a dollar figure on it, the Kantar survey quantifies the cost to households at $3.1 billion – a staggering figure considering the current cost of living crisis and high food prices.

Research by Love Food Hate Waste New Zealand in 2018 puts the figure higher still, at 157,000 tonnes.

This doesn’t even include food lost on the commercial side of the supply chain; during harvest, manufacture, transport, and storage – a figure which there is little data on. Professor Miranda Mirosa of the University of Otago’s Department of Food Science says, “The publicly available New Zealand retail data shows supermarkets create 60,500 tonnes of unsold food annually.”

This is just one dataset from one sector. She also notes New Zealand is still “woefully short” of properly understanding what is wasted in the food supply chain.

Another figure which gives us a glimpse of this loss, but from a local perspective, comes from Hawke’s Bay food rescue organisation Nourished 4 Nil. They report having donated 139 tonnes of food in May of this year alone. This food is mostly donated by producers, supermarkets, and retailers for reasons such as damaged packaging or being close to best before dates but is still fit for human consumption.

Where to start?

Comprehending a problem is the first step to tackling it and as Miranda points out, New Zealand has little understanding of our level of food waste. This, she says, is because we haven’t had a national definition for it, and no one has done a whole supply chain investigation.

Things are set to change though, with a technical definition for food waste due to be announced soon by Government, she says. Work can then begin to properly measure it.

Miranda’s university research group is about to start a project, commissioned by the Ministry for the Environment, to establish a baseline measure of food loss in Aotearoa. The results are expected early next year.

I for one am very interested to see what their work uncovers.

Legislative work has also been happening at the other end of the food waste pipeline. In March Government announced that by 2030 all district and city councils must provide food scrap collections to households in urban areas.

This will not only keep this food waste out of landfill but means it can be repurposed into fertiliser or other high-value products. I would also argue having a separate bin for food waste is a potent behaviour change tool as it makes households more aware of how much food is being lost.

Auckland is in the process of rolling out their collection system, and Western Bay of Plenty has already rolled out theirs.

Alternatives to landfill

We’re fortunate in Hawke’s Bay to have a commercial composter BioRich on our doorstep. Cyclone Gabrielle had a severe impact on their operations in Awatoto, but they were awarded $1 million from the Government’s Waste Minimisation Fund to help get the business back up and running.

The destination for Auckland’s food scraps collection is EcoGas, based in Reporoa, which uses organic waste in the country’s first anaerobic digestion system. It creates biogas, which is used to generate electricity, heat water for local glasshouses, make biomethane which is fed into New Zealand’s natural gas network, and create fertiliser for over 3,000 hectares of crop production.

The plant also makes bottled, food-grade carbon dioxide which is needed by our food producers and is currently imported into New Zealand.

EcoGas was also instrumental in diverting close to 500 tonnes of spoiled food from landfill after Hawke’s Bay was devastated by the cyclone. Managing Director Andrew Fisher says they worked with Napier City Council to collect spoiled food from residents. They also collected from manufacturing facilities and supermarkets, with all the material being transported via Palmerston North due to SH5 being closed at the time.

EcoGas has the automated mechanical facilities to unpack packaged food and treat meat to international standards before it is fed into their digester, Andrew says.

From food rescue to production

Some food waste comes from production being out of kilter with demand, produce not meeting supermarket standards, or is a byproduct of food production. There are businesses and organisations aiming to change this.

One startup, EatKinda, is aiming to create ice-cream out of imperfect cauliflower that doesn’t make the grade for sale in supermarkets. During their initial trial in 2022, they diverted 468 kilograms from food waste – approximately 310 cauliflower florets that would’ve otherwise have gone unpicked.

Although their recent sellout promotion with Hell Pizza ended up using commercial cauliflower due to crop loss in the Auckland floods, this is still their aim going forward.

Recently NZ-grown fast food chain Burger Fuel partnered with food rescue organization Citizen Collective to make cherry cola from rescued cherries and a byproduct of rum making. Citizen Collective also makes beer from rescued bread.

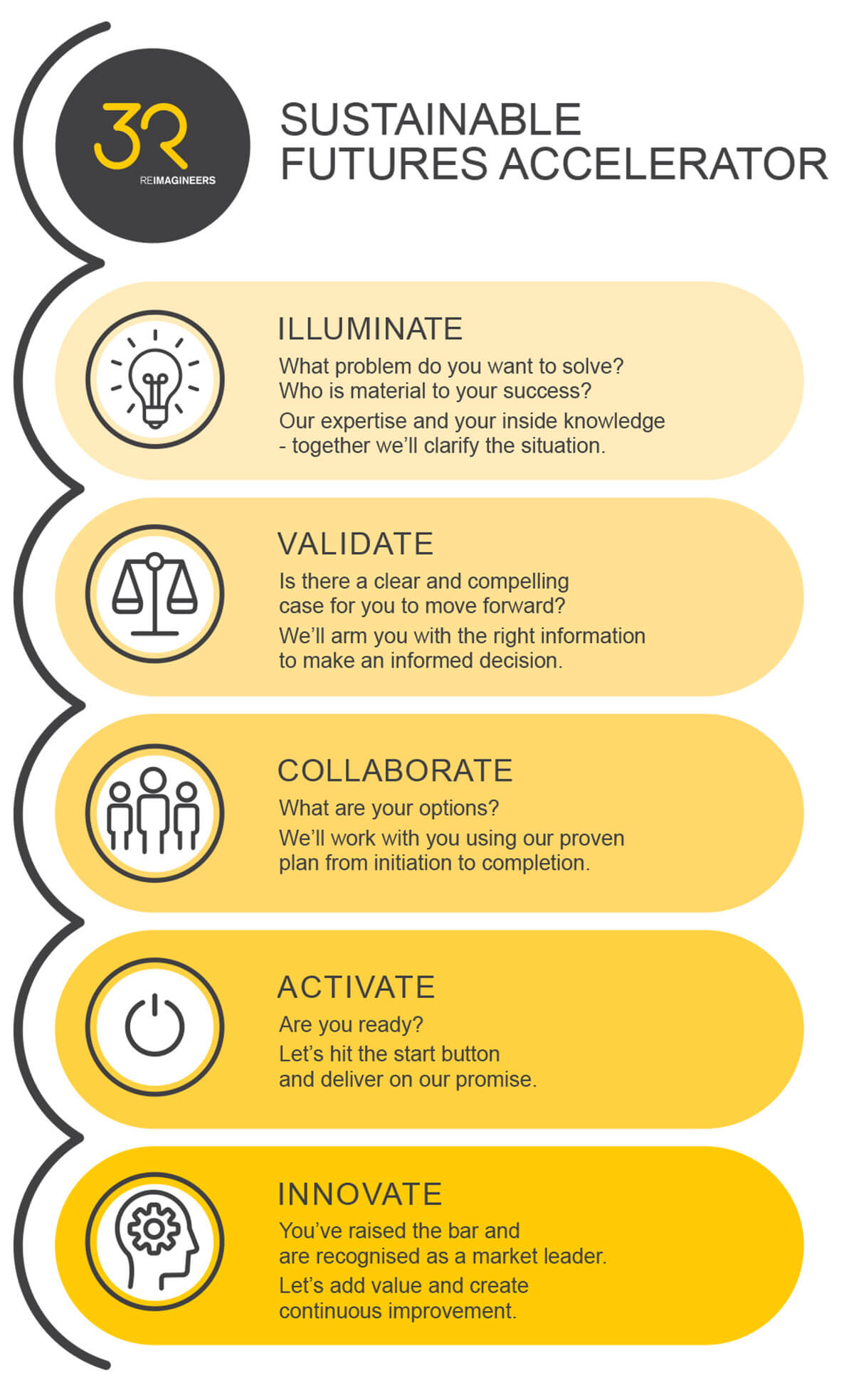

Here in Hawke’s Bay, interns based with us at 3R worked over the summer on the Sustainable is Attainable project, looking at creating high value products out of byproducts from corn and oat milk production.

The good thing about food waste is it’s something everyone can tackle, from producers through to consumers. Pass the cauliflower ice-cream.